IFS Reports

Key findings [1]

-

Pensioner incomes largely depend on pensions, from both state and private sources, 54% of pensioners received income from private pensions in 2019/20 compared with 50% in 2002/03. Pension incomes are driven by a combination of factors such as policy reforms, while state pension entitlements in particular have been subject to substantial reform.

-

Between 2002/03 and 2011/12, median pensioner incomes grew by 22% after inflation. Poorer pensioners’ incomes were growing at a similar rate to average pensioner incomes prior to 2011 leading to relative pensioner poverty falling from 25% in 2002/03 to 13% in 2011/12.

-

Since 2011, average pensioner incomes have been growing at a similar rate to working-age incomes. Average incomes for pensioners, which are now very similar to average incomes below state pension age, grew by 12% from 2011/12 to 2022/23, driven by higher state and private pension incomes.

-

Since 2011, income growth for poor pensioners has lagged behind the population as a whole, rising by only 5% after inflation. This is in part because poor pensioners have benefited from neither the rises in employment income nor the rises in private pension income.

-

This slow income growth for poorer pensioners means that relative pensioner poverty rose from 13% in 2011/12 to 16% in 2022/23, equivalent to an increase of 300,000 pensioners.

-

Growth in state pension incomes has been offset in large part by falling levels of other benefits - higher state pensions increase pensioner incomes, making them increasingly ineligible for further means-tested state support - state pensions being the main source of income.

-

Since the onset of the pandemic (2019/20 to 2022/23), lower income pensioners experienced higher income growth than higher income pensioners, as they received more state support during the cost-of-living crisis. However, these income poverty statistics understate the financial difficulties faced by poorer pensioners who were more exposed to sharp rises in gas, electricity and food prices.

-

Before the pandemic, the average incomes of pensioners were pushed up in part by rising state pension incomes. This was due to a combination of triple lock indexation of the basic state pension since 2011 and the introduction of the new state pension in 2016.

Gender state pension gap

-

Successive generations of women have spent more years in paid work and reforms in 2010 and 2016 also substantially boosted the state pension incomes of many women (pensions credits for time spent out of work raising children). As a result, the gender gap in state pension incomes has all but disappeared for those born after 1950.

-

Despite this, changes have not led to large falls in relative income poverty for these women compared with previous generations at the same age, as higher state pensions have led to falls in eligibility to other benefits for low-income families.

Conclusion

-

Recent decades have seen an increase in average pensioner incomes (state and private), primarily driven by state and private pensions policy reforms.

-

The benefit system is more generous for pensioners in low-income households than for low-income working-age households, although benefit take-up remains a challenge.

-

Since 2011, growth in private pension incomes and state pensions boosted average pensioner incomes but not poorer pensions, creating income equality. Also, growth in state pension incomes for poor pensioners has been largely cancelled out by reduced eligibility for means-tested benefits and therefore reduced the state support available to these households.

-

Reforms to the state pension have particularly benefited groups with historically lower pension incomes, such as married women. However, these reforms have not significantly reduced relative poverty rates, as they were not particularly aimed at low-income households but rather at women who had been caring for young children during their working life.

According to the Centre for Ageing Better, around two million UK pensioners are living in poverty. [2] -

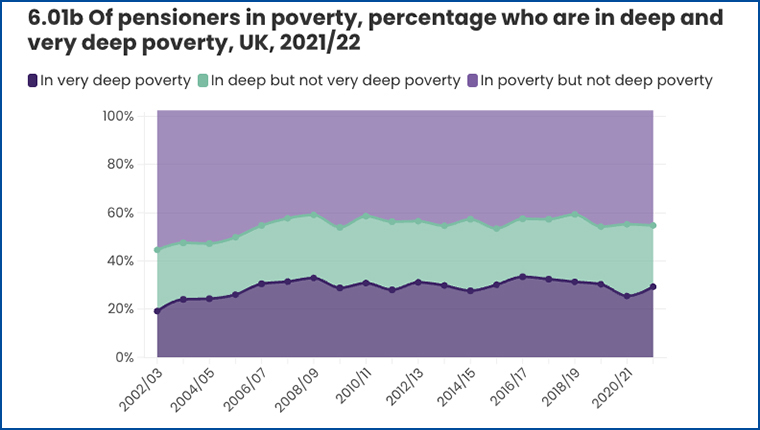

Of these 2.1 million pensioners, 55% are in deep poverty and 29% in very deep poverty. That is 16 % of all older people in poverty or one in six of everyone in later life.

-

According to the Department for Work and Pensions’ (DWP) March statistics, there were 16% of pensioners in ‘relative’ low income after housing costs at year end 2023, with 19% being so before housing costs. [3]

-

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation statistics show that 18% of the retired population are in poverty. [4]

-

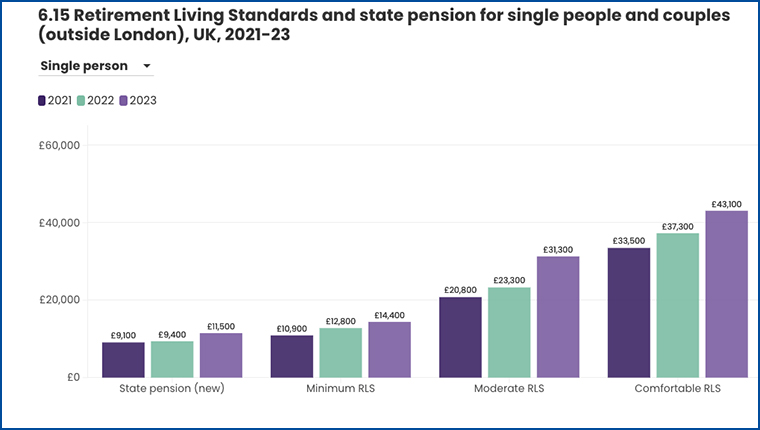

Pensions and Lifetime Savings Association (PLSA) calculations show that the annual minimum income standard for a single pensioner should be £14,400 a year. [5]

-

With the state pension currently £11,502.40 a year, pensioners reliant on the state pension would fall short of this standard by around £3,000 and need to bridge that gap in order to achieve a minimum quality of life in retirement. The proposed increase to state pension for 2025/26 is £12,000 and therefore the minimum standard would still be short by approximately £2,000.

-

The Centre for Ageing Better puts this minimum shortfall at £80 a week for couples and £50 a week for single pensioners, having more than doubled for pensioner couples and almost quadrupled for single pensioners since the start of the cost-of-living crisis. [6]

Equalities

-

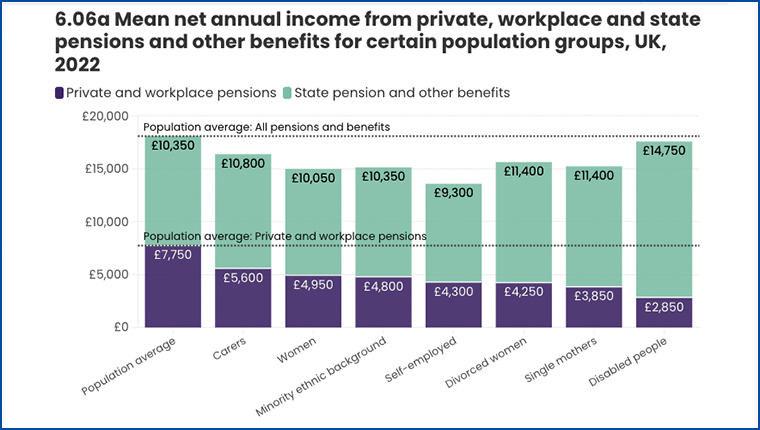

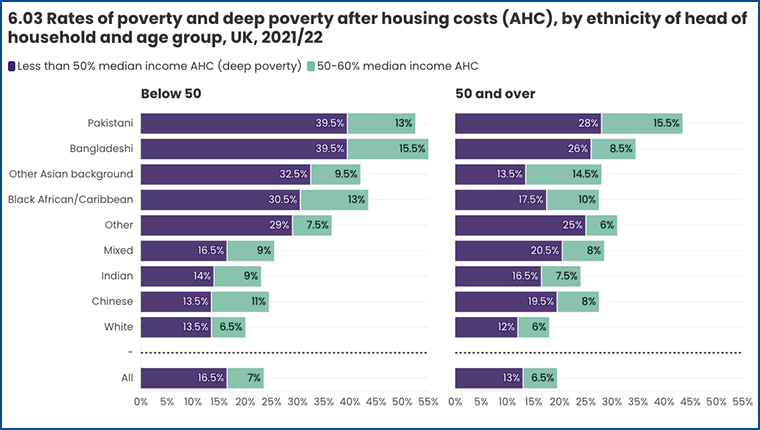

Women, single people, ethnic minorities, the self-employed, those with disabilities and those who are still paying for housing costs in retirement are at greater risk of being in poverty as a pensioner.

-

Single pensioners account for the majority of households largely reliant on the state pension, with a clear gender imbalance, as more than three times as many women (580,000) as men (180,000) rely primarily on the state pension.

-

At-risk social factors mean that women are more vulnerable to an impoverished retirement, with 17% of women in later life currently in poverty compared to 15% of men, as are those who are disabled or self-employed. Single people are also at risk, with 25% compared to 14% of couples in poverty at retirement. [7]

-

A similar number of pensioners from ethnic minorities also face an impoverished retirement - 25% of Asian and Asian British older people are in poverty, as are 26% of those of a Black/African/Caribbean/Black British background. [8]

Footnotes

[1] https://ifs.org.uk/sites/default/files/2024-07/How-have-pensioner-incomes-and-poverty-changed-in-recent-years_2_0.pdf

[2] https://ageing-better.org.uk/the-state-of-ageing-2023-4

[3] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/cost-of-living-support-impact-on-households-below-average-income-fye-2023-low-income-statistics/cost-of-living-support-impact-on-households-below-average-income-fye-2023-low-income-statistics

[4] https://www.jrf.org.uk/deep-poverty-and-destitution/what-protects-people-from-very-deep-poverty-and-what-makes-it-more

[5] https://www.fca.org.uk/news/speeches/future-pensions-act-today-plan-tomorrow

[6] https://ageing-better.org.uk/news/last-weeks-budget

[7] Morgan Vine, the Centre for Ageing Better research

[8] Ibid.

Anonymous feedback

If you require a response from us, please DO NOT use this form. Please use our Contact Us page instead.

In our continued efforts to improve the website, we evaluate all the feedback you leave here because your insight is invaluable to us, but all your comments are processed anonymously and we are unable to respond to them directly.