NASUWT advice to address menopause health and raise awareness

Introduction

What is the menopause?

Signs and symptoms of the menopause

Possible treatments

Looking after yourself and maintaining a healthy lifestyle

The menopause as an equality issue

The menopause as a gender-sensitive health and safety issue

The menopause as a workplace issue

Addressing workplace issues

What can we expect from employers?

What support can members expect from NASUWT?

Relevant policies

Monitoring and reporting procedures

Model menopause policy

Introduction

Employers have been slow to recognise that women [1] of menopausal age may need special consideration. For too long, it has simply been seen as a private matter.

As a result, it is rarely discussed and many managers will have no awareness of the issues involved. This means that many women feel they have to hide their symptoms and will be less likely to ask for the adjustments that may help them.

The majority of women will experience some or all of the symptoms of the menopause at some point in their lives and NASUWT believes that, as teaching is a predominately female profession, addressing the menopause should be a high priority in all workplaces.

It is important that all trade union representatives, including male representatives, feel confident to discuss the menopause with members. This toolkit aims to help representatives have a greater understanding of the menopause and provides a workplace framework for negotiation and consultation when working with employers.

By highlighting employers’ legal responsibilities and stating the legal context framework supporting menopause casework, it should also provide support for members and those representing members. However, because everyone’s experience of the menopause is different, the most important thing is to listen to the individual.

For many reasons, a person may feel unable to disclose symptoms of the menopause to their employers and therefore it is imperative that school and college representatives have a good understanding of the menopause and also deal sensitively with members’ concerns.

Representatives should be particularly mindful that this could be the case for supply teachers as they may feel particularly vulnerable.

What is the menopause?

The menopause is a natural part of ageing which usually occurs between 45 and 55 years of age. It occurs as a direct result of a woman’s oestrogen levels declining. In the UK, the average age for a woman to reach menopause is 51. A woman is officially described as post-menopausal when her ovaries are no longer responsive and when she has not had a period for 12 months.

The perimenopause is the period of hormonal change leading up to the menopause. This is the time when many women start to experience symptoms. The perimenopause can often last for four to five years, although for some women it may continue for many more years or for others last just a few months.

In general, periods usually start to become less frequent over this time. Sometimes menstrual cycles become shorter, periods may become heavier or lighter or women may notice that the odd period is missed until eventually they stop altogether. Some women report that during the perimenopause, they experience worse symptoms than the menopause.

Some women experience sudden menopause after surgery, chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

It is estimated that around one in every 100 women will experience a premature menopause (before the age of 40).

The menopause affects every woman differently and so there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution to it.

Some women experience few symptoms while others experience such severe symptoms that it impacts negatively on both their home and working lives.

Signs and symptoms of the menopause

The following is merely a guide to some of the signs and symptoms women may experience as part of the menopause. Some women may suffer with conditions that are exacerbated by the menopause, such as osteoarthritis and migraine. This will be explored further in The menopause as an equality issue section below.

Signs and symptoms may include:

Vasomotor symptoms

-

Hot flushes and night sweats

Psychological effects of hormone changes

-

Low mood/mood swings

-

Poor memory and concentration

-

Insomnia

-

Loss of libido

-

Anxiety/panic attacks

Physical symptoms

-

Headaches

-

Fatigue

-

Joint aches and pains

-

Palpitations

-

Formication (creeping skin)

-

Insomnia

Sexual symptoms

-

Reduced sex drive

-

Painful sex/vaginal dryness

-

Urinary tract infections

-

Vaginal irritation

Consequences of oestrogen deficiency

-

Obesity, diabetes

-

Heart disease

-

Osteoporosis/chronic arthritis

-

Dementia and cognitive decline

-

Cancer

Please note, this is not an exhaustive list.

Many women may also find that their symptoms are connected. For example, sleep disturbance, which is common during the menopause, may lead to a whole plethora of other serious conditions.

The length of time that women experience symptoms of the menopause can vary between women. Again, there is no one answer for all.

Symptoms can begin months or years before a woman’s periods stop.

The perimenopause is usually expected to last around four or five years, but it can be much shorter or longer. During this time, many women begin to experience painful, intermittent and heavy periods. As a teacher, it is therefore important to raise this issue with management if adjustments need to be put in place, such as having access to a toilet and shower facilities.

According to the NHS, on average, a woman continues to experience symptoms for around four years after their last period, but around 10% of women continue to experience symptoms for up to 12 years after their last period and 3% will suffer for the rest of their lives. With teachers remaining in the classroom well into their sixties, it is imperative that caseworkers are aware of this and are not afraid to raise it as an issue with women members seeking help and support for other, seemingly unrelated, concerns.

It is also important to recognise that beyond the menopause, post-menopausal women can be at increased risk of certain conditions due to a decrease in hormones. These include osteoporosis and heart disease.

The British Menopause Society (2016) estimated that 50% of women aged between 45 and 65 who had experienced the menopause in the previous ten years had NOT consulted a healthcare professional about their menopausal symptoms.

This was despite:

-

42% of women feeling that their symptoms were worse or much worse than they expected;

-

50% of women believed the menopause had impacted on their home life; and

-

more than a third believed the menopause had impacted on their work life.

Caseworkers should be mindful that a member may not believe that any workplace problems could be attributed to the menopause and therefore may not have sought medical help. There is still a very prevalent mindset that women should ‘just get on with it’, but for some women, this is not an option.

Possible treatments

Hormone replacement therapy

Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) is a treatment that relieves symptoms by replacing the oestrogen your body stops making after the menopause. Many women also need to take a progestogen alongside oestrogen, known as combined HRT.

Some women also take testosterone as part of their HRT. Oestrogen is available as a skin patch, gel applied to the skin or a tablet. HRT remains the most effective treatment to relieve symptoms.

Women who have had their wombs removed but still have ovaries should seek help from their GP as some medication will not be appropriate.

Many women find their symptoms improve within a few months of starting HRT and feel like they have their ‘old life’ back, improving their overall quality of life. Hot flushes and night sweats usually stop within a few weeks of starting HRT.

Many of the vaginal and urinary symptoms usually resolve within three months, but it can take up to a year in some cases.

You should also find that symptoms such as mood changes, difficulty concentrating, aches and pains in your joints and the appearance of your skin will also improve.

There is some evidence that taking HRT, particularly oestrogen-only HRT, reduces your risk of cardiovascular disease.

The benefits are greatest in women who start HRT within ten years of their menopause.

Taking HRT can help prevent and reverse bone loss, even for women who take lower doses of HRT, so it can reduce your risk of bone fracture due to osteoporosis. Your risk of other diseases will reduce.

Studies have shown that women who take HRT also have a lower future risk of type-2 diabetes, osteoarthritis, bowel cancer, depression and dementia.

There are risks and side effects which can include nausea, some breast discomfort and leg cramps, so members are advised to speak to a medically qualified practitioner for further help and support.

From 1 April 2023, women in England will be able to access cheaper HRT to help with menopause symptoms.

Not all HRT medicines are covered, so members are encouraged to check if theirs are covered. Further information can be found on the NHS website.

It continues to be free in Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland.

HRT may not be suitable, or a specialist opinion may be needed, if you:

-

have a history of breast cancer, ovarian cancer or womb (uterus) cancer;

-

have a history of blood clots, tablet HRT is not recommended but taking HRT through the skin can be considered;

-

have a history of heart disease or stroke;

-

have untreated high blood pressure - your blood pressure will need to be controlled before you can start HRT;

-

have liver disease;

-

are pregnant or breastfeeding.

In these circumstances, a different type of medication may be prescribed to help manage your menopausal symptoms:

-

body-identical and bioidentical hormones - body-identical, bioidentical hormones and ‘other’ herbal treatments are non-regulated so assistance should always be sought from a GP;

-

testosterone - some women experience a decrease in their sex drive and testosterone replacement can help with this;

-

oestrogen creams/tablets - these help with conditions such as vaginal dryness;

-

cognitive behavioural therapy - cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) helps people manage their problems by encouraging a recognition of how their thoughts affect feelings and behaviour. It aims to break problems down into smaller parts, making them easier to manage;

-

other treatments - things such as yoga and meditation have improved the symptoms for some people.

Yoga can help manage the physical and psychological symptoms that many women experience during the transition from perimenopause to menopause. It can also improve their long-term physical and mental health for post-menopausal women and help to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease. Yoga can help retain muscle flexibility, general mobility and balance.

However, the greatest benefits of yoga will be experienced if it is included as part of a holistic approach to health and wellbeing that includes nutrition, lifestyle and medical advice from your doctor and other health professionals.

Looking after yourself and maintaining a healthy lifestyle

Women may want to consider a Menopause Fitness Plan, which should include aerobic exercise, strength training and relaxation exercises.

Women often feel they have lost control of their bodies during this period of their lives and exercise is a great way to help regain some of that control, especially if it is combined with the great outdoors!

If work is proving stressful, take time out for yourself. Do something you enjoy that lifts your mood, such as yoga, having an aromatherapy massage or just spending time with loved ones.

As with all advice, consult your GP before undertaking a new training regime

The menopause as an equality issue

The Equality Act 2010 (England, Scotland, Wales)

Northern Ireland:

-

Northern Ireland - Sex Discrimination Order 1976 (Amendment) Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2008;

-

Disability Discrimination Act 1995 (NI);

-

Section 75 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998;

-

Sex Discrimination (Gender Reassignment) Regulations (Northern Ireland) 1999.

The menopause affects all women at some stage, be that earlier or later in life, and it can often indirectly affect their partners, families and colleagues as well. The Trades Union Congress (TUC) estimate that in the UK, around 13 million or around one in three women are either currently going through or have reached the menopause.

There are also many younger women receiving treatments for common conditions such as endometriosis (estimated to affect around one in ten women of reproductive age) and infertility (which affects around one in seven couples). Although, strictly speaking, these women may not be menopausal, many of them will experience a temporary ‘artificial’ menopause and menopausal symptoms whilst receiving treatments which may be carried out over weeks, months or years intermittently.

It is difficult to gauge statistically the number of people who experience the menopause from the non-binary, transgender or intersex communities.

In some cases, trans people may be affected by menopausal symptoms due to the natural menopause process, or treatments or surgeries. The experience and perceptions of the menopause may be different for those among these communities.

Trans men (those who identify as male, but were assigned female at birth) will experience a natural menopause if their ovaries remain in place and no hormone therapy is given. However, if the ovaries and uterus are surgically removed, then a trans man will experience menopausal symptoms at whatever age that occurs. Symptoms may be reduced or complicated if hormone therapy, such as the male hormone testosterone, is in place.

Trans women (those who identify as female, but were assigned male at birth) undertaking hormone therapy will usually remain on this for life, and should generally experience limited ‘pseudo’ menopausal (menopausal-like) symptoms unless hormone therapy is interrupted or hormone levels are unstable.

Black and minority ethnic (BME) women and the menopause

There is limited research in this area and we have to look to America for a specific report on the menopause and BME women, but it appears there may be a slight variation in the average age at which the menopause takes place.

Black women may experience more symptoms than white women and start the menopause earlier and Asian women may experience slightly fewer symptoms and start the menopause later. It is unclear to what extent these differences are caused by social, economic, language and cultural factors rather than a woman’s ethnic origin. Women who do not have English as a first language may have more difficulty in communicating symptoms or difficulties they are experiencing. Racism at work can increase work-related stress, which may worsen some menopausal symptoms.

Research by the TUC has also shown that BME workers are more likely than white workers to be in insecure work, such as zero-hours or casual contracts. This could also potentially mean that BME women on insecure contracts are reluctant to raise the issue of their menopausal symptoms or ask for adjustments at work because of concerns that doing so may negatively affect their job security.

It is important for union representatives to be aware of how the experience of the menopause may vary for different people, particularly those with certain protections, as defined by the Equality Act 2010. The Act has nine ‘protected characteristics’: age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion and belief, sex, and sexual orientation.

The menopause itself is not covered by the Equality Act 2010, but the health conditions that arise from it, or are made worse by it, may be.

Section 6 of the Equality Act defines a disability as ‘a physical or mental impairment which has a substantial and long-term adverse effect on a person’s ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities.’

In deciding whether the member’s condition would be covered by the Equality Act, they should be advised to seek medical confirmation from their GP and or their Occupational Health Provider.

The menopause is still largely uncharted territory and employers must be careful to avoid types of conduct that are unlawful as defined by the Equality Act. These are:

-

direct discrimination;

-

indirect discrimination;

-

harassment;

-

victimisation;

-

failure to make reasonable adjustments;

-

discrimination arising from disability;

-

discrimination based on association or perception, as defined under the Equality Act 2010, Disability Discrimination Act 1995 (NI).

Please note, each of the prohibited conducts above has a specific LEGAL definition as distinct from any colloquial or common understanding.

This could potentially cover sex discrimination, age discrimination, gender reassignment discrimination, and disability discrimination.

Reasonable adjustments (as defined by the Equality Act 2010, s.20)

The duty to make reasonable adjustments requires employers to take positive action to remove certain disadvantages to disabled people posed by working practices and the physical features of premises.

PCP

A PCP is where a provision, criterion or practice is applied by the employer that puts a group or groups of people at a substantial disadvantage in comparison with those who do not have a protected characteristic. For example, decisions such as not allowing flexible working for employees. This could disadvantage women and disabled employees. For a menopausal woman, we would challenge this under the provisions of the Equality Act.

Here, the employer must take such steps as it is reasonable to take to avoid the disadvantage.

If the member has been classed as disabled by a medical professional, then such decisions as ‘no part-time contracts’ in workplaces could potentially be challenged under the Equality Act, as it places women experiencing the menopause at a substantial disadvantage.

Where a physical feature of the employer’s premises puts a disabled person at a substantial disadvantage in comparison with those who are not disabled: again, the employer must take such steps as are reasonable to avoid the disadvantage. An example of this could be the refusal to allow a teacher to work in a classroom close to toilets because teachers in departments have to be grouped together.

Where a disabled person would, but for the employer’s provision of an auxiliary aid, be put at a substantial disadvantage in comparison with those who are not disabled, the employer must take such steps as are reasonable to provide the auxiliary aid.

Unfortunately, the Act fails to define what it means by ‘auxiliary aid’. NASUWT considers such things as access to drinking water, toilets and showers included.

The duty to make reasonable adjustments is one of the few instances where positive discrimination is permitted.

Generally, treating one person more favourably than another because they have a protected characteristic is prohibited under the Equality Act 2010, unless an occupational requirement applies.

Positive discrimination because of a person’s disability is allowed, and may sometimes be required, if there is a duty to make reasonable adjustments. For example, appointing a disabled employee to an alternative post, even if that employee is not the best candidate (Archibald v Fife Council [2004]).

Examples of reasonable adjustments for people experiencing the menopause

-

Access to cold drinking water

-

Access to toilets

-

Access to adjustable temperature control

-

Adequate and flexible breaks

-

Possible (temporary) job alternatives

-

Flexible working (may be temporary)

-

Time to attend medical appointments

Members should be advised to submit requests for Reasonable Adjustments to the employer, under the legal obligations of the Equality Act 2010.

If the request is denied, members will need to consider raising a grievance against the employer for failure to implement reasonable adjustments.

As with all potential discrimination cases, guidance should be sought from the Local Association (LA) Secretary, National Executive Member and or National/Regional Centre if the member wishes to progress the grievance.

The Public Sector Equality Duty

Since 2012, schools have been required to publish information to show how it complies with the Public Sector Equality Duty (PSED) and set equality objectives.

Every school is required to update that published information at least annually.

Under the PSED, school management and governing bodies are required to have ‘due regard’ when making decisions and developing policies to the need to:

-

eliminate discrimination, harassment, victimisation and other conduct that is prohibited under the Equality Act 2010;

-

advance equality of opportunity between people who share a protected characteristic and people who do not share it; and

-

foster good relations across all protected characteristics - between people who share a protected characteristic and people who do not share it.

Having ‘due regard’ means

-

a school must assess decisions and gauge their equality;

-

equality implications should be considered before and at the time a policy is developed;

-

each strand of the duty should be considered consciously and separately (eliminating discrimination is different to advancing equality);

-

the risk of any adverse impact that might result from a policy or decision should be assessed;

-

this is not just a box-ticking exercise; and

-

schools must carry out this duty themselves - and record all the steps they have taken to meet the duty.

For more information, see our Public Sector Equality Duty advice.

By fostering safer and fairer workplaces for women working through the menopause, employers are more likely to retain the skills and talents of experienced and skilled workers and benefit from increased morale and wellbeing among staff.

Caseworkers should acknowledge that for many reasons, people’s individual experiences of the menopause may differ greatly and that no assumptions should be made when dealing with casework.

The menopause as a gender-sensitive health and safety issue

TUC Gender in Occupational Safety and Health

The Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 and Health and Safety, NI Order, 1978 requires employers to ensure the health, safety and welfare of their workers and take measures to control any risk that is identified.

Employers are required to carry out risk assessments under the Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1999 (UK wide) and The Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2000, NI Regulation 3(1), which should include any specific risks to menopausal women.

The law states that those carrying out risk assessments must have had ‘sufficient training and experience or knowledge and other qualities’.

Men and women have physical, physiological and psychological differences that can determine how risks affect them. Women are also the ones who give birth and, in most cases, look after children or assume other family caring responsibilities. The employment experiences of men and women also differ because women and men are still often found in different occupations, or treated differently by employers. This means that men still tend to predominate more visibly heavy and dangerous work, such as construction, where there are high levels of injury from one-off events. Women, on the other hand, still tend to work in areas where work-related illness arises from less visible, long-term exposures to harm.

In the past, less attention has been given to the health and safety needs of women. The traditional emphasis of health and safety has been on risk prevention in visibly dangerous work that is largely carried out by men in sectors such as construction and mining, where inadequate risk control can lead to fatalities. On the other hand, the historic focus for women (particularly pregnant women) has been on prohibiting certain types of work and exposures or has been based on an assumption that the kind of work that women do is safer.

Because of this, research and developments in health and safety regulation, policy and risk management have been primarily based on work traditionally done by men, while women’s occupational injuries and illnesses, such as work-related stress, musculoskeletal disorders (MSD) and dermatitis have been largely ignored, under-diagnosed, under-reported and under-compensated.

This means that, even today, occupational health and safety often treats men and women as if they were the same, or makes gender-stereotypes, such as saying women do lighter work or that men are less likely to suffer from work-related stress. In contrast, a gender-sensitive approach acknowledges and makes visible the differences that exist between male and female workers, identifying their differing risks and proposing control measures so that effective solutions are provided for everyone.

Being aware of the issues relating to gender in occupational health and safety ensures unions strive to ensure that workplaces are safer and healthier for everyone.

The menopause is a recognised occupational health issue and should therefore be addressed at school and college level. NASUWT believes that all workplaces should have an effective gender sensitive policy that is entirely consistent with the statutory provisions of:

England, Scotland and Wales

-

Health and Safety at Work Act, 1974;

-

The Workplace (Health, Safety and Welfare) Regulations 1992;

-

The Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1999, GB Regulations 4;

-

The PSED introduced by the Equality Act 2010 (England, Scotland and Wales);

-

Equality Act 2010.

Northern Ireland

-

The Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2000, NI Regulation 3(1);

-

Health and Safety, NI Order, 1978;

-

Sex Discrimination Order 1976 (Amendment) Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2008;

-

Disability Discrimination Act 1995 (NI);

-

Section 75 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998;

-

Sex Discrimination (Gender Reassignment) Regulations (Northern Ireland) 1999.

The law requires employers to assess the risk of stress-related ill health arising from work activities in the same way as any other hazard. All workplaces should have an effective gender-sensitive policy that is consistent with statutory provisions.

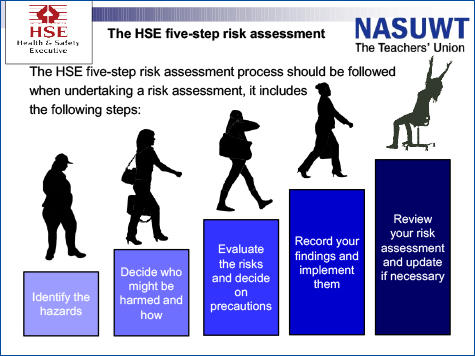

Risk assessments should consider the specific needs of menopausal women and ensure that the working environment will not make their symptoms worse. Issues that need looking at include temperature, ventilation, toilet facilities and access to cold water. It is important that workplace stress is also considered and addressed properly using the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) stress management standards.

The HSE stress management standards

NASUWT advice on HSE standards

The menopause as a workplace issue

It is important that trade unions raise the issue in the workplace and make sure that employers are aware of their responsibilities to ensure that conditions in the workplace do not make the symptoms of the menopause worse.

It is also important that women experiencing the menopause know where and who to go to for help and support in the workplace and also feel confident to raise issues in the workplace.

Union representatives play a key role in supporting members and helping to challenge workplace discrimination and harassment, including that linked to the menopause.

Workplace Representatives should consider the following in the workplace:

Get organised

Consult with members to find out what they need in school/college.

Set up a Health and Safety Committee

If two or more trade unions submit a request to the employer in writing, they must by law set up a Health and Safety Committee within an agreed timeframe. The menopause could be put on the agenda.

Women members should consider becoming Health and Safety Representatives

Our Health and Safety Rep page provides further information.

Consider a workplace Campaign/Support Group

This is something members can do for themselves. Maybe negotiate with employers for a quiet meeting room with access to tea/coffee/water.

Have a workplace policy

This could be a ‘gender-sensitive’ health and safety policy and/or a menopause policy. It would need to follow the same consultation process as any other policy.

Addressing workplace issues

The grid below has been adapted from a TUC model and has been specifically tailored to meet teachers’ needs. It is not an exhaustive list and members should use the criteria to meet their particular needs.

| Symptom | Examples of workplace factors which could worsen or interact with symptoms | Suggested adjustments |

|---|---|---|

| Daytime sweats, hot flushes, palpitations | Lack of access to rest breaks or suitable break areas. Hot flushes and facial redness may cause women to feel self-conscious, or the sensation may affect concentration or train of thought. | Be flexible about additional breaks. Allow time out and access to fresh air. Ensure a quiet area/room is available. Ensure cover is available so workers can leave their posts if needed. |

| Night time sweats and hot flushes. Insomnia or sleep disturbance | Rigid start/finish times and lack of flexible working options may increase fatigue at work due to lack of sleep. | Consider temporary adjustment of hours to accommodate any difficulties. Allow flexible working. Provide the option of alternative tasks/duties. Make allowance for potential additional need for sickness absence. Reassure workers that they will not be penalised or suffer detriment if they require adjustments to workload or performance management targets. |

| Urinary problems; for example, increased frequency, urgency, and increased risk of urinary infections | Lack of access to adequate toilet facilities may increase the risk of infection and cause distress, embarrassment and an increase in stress levels. Staff member may need to access toilet facilities more frequently, may need to drink more fluids and may feel unwell. |

Ensure easy access to toilet and washroom facilities. Allow for more frequent breaks during work to go to the toilet. Ensure easy access to supply of cold drinking water. Take account of peripatetic workers schedules and allow them to access facilities during their working day. Make allowances for potential additional need for sickness absence. |

| Irregular and/or heavy periods | Lack of access to adequate toilet facilities may increase the risk of infection and cause distress, embarrassment and an increase in stress levels. Staff member may need to access toilet and washroom facilities more frequently. | Ensure easy access to well-maintained toilet and washroom or shower facilities. Allow for more frequent breaks in work to go to the toilet/washroom. Ensure sanitary products readily available. Take account of peripatetic workers schedules and allow them to access facilities during their working day. Ensure cover is available so staff can leave their posts if needed. |

| Skin irritation, dryness or itching | Unsuitable workplace temperatures and humidity may increase skin irritation, dryness and itching. There may be discomfort, an increased risk of infection and a reduction in the barrier function of skin. |

Ensure comfortable working temperatures and humidity. Ensure easy access to well maintained toilet and washroom or shower facilities. |

| Muscular aches and bone and joint pains | Lifting and moving, as well as work involving repetitive movements or adopting static postures, may be more uncomfortable and there may be an increased risk of injury. | Make any necessary adjustments through review of risk assessments and work schedules/tasks and keep under review. Consider providing alternative lower-risk tasks. Follow Health and Safety Executive (HSE) guidance and advice on manual handling and preventing MSDs (musculoskeletal disorders). |

| Headaches | Headaches may be triggered or worsened by many workplace factors such as artificial lighting, poor air quality, exposure to chemicals, screen work, workplace stress, poor posture/unsuitable workstations, unsuitable uniforms or workplace temperatures. | Ensure comfortable working temperatures, humidity and good air quality. Ensure access to natural light and ability to adjust artificial light. Allow additional rest breaks. Ensure a quiet area/room is available. Carry out Display Screen Equipment (DSE) and stress risk assessments. |

| Dry eyes | Unsuitable workplace temperatures/humidity, poor air quality and excessive screen work may increase dryness in the eyes, discomfort, eye strain and increase the risk of infection. | Ensure comfortable working temperatures, humidity and good air quality. Allow additional breaks from screen based work. Carry out DSE risk assessments. |

Psychological symptoms, for example:

|

Excessive workloads, unsupportive management and colleagues, perceived stigma around the menopause, bullying and harassment and any form of work-related stress may exacerbate symptoms. Stress can have wide-ranging negative effects on mental and physical health and wellbeing. Performance and workplace relationships may be affected. |

Carry out a stress risk assessment and address work-related stress through implementation of the HSE’s management standards. Ensure that workers will not be penalised or suffer detriment if they require adjustments to workload, tasks or performance management targets. Ensure that managers understand the menopause and are prepared to discuss any concerns that staff may have in a supportive manner. Ensure managers have a positive attitude and understand that they should offer adjustments to workload and tasks if needed. Allow flexible/home working. Make allowance for potential additional need for sickness absence. Ensure that staff are trained in mental health awareness. Raise general awareness of issues around the menopause so colleagues are more likely to be supportive. Provide opportunities to network with colleagues experiencing similar issues (menopause action and support group). Ensure a quiet area/room is available. Provide access to counselling services. |

Psychological symptoms:

|

Certain tasks may become more difficult to carry out temporarily; for example, learning new skills (may be compounded by lack of sleep and fatigue), performance may be affected and work-related stress may exacerbate these symptoms. Loss of confidence may result. | Carry out a stress risk assessment and address work-related stress through implementation of the HSE’s management standards. Reassure workers that they will not be penalised or suffer detriment if they require adjustments to workload or performance management targets. Ensure that managers understand the menopause and are prepared to discuss any concerns that staff may have in a supportive manner. Ensure managers have a positive attitude and understand that they should offer adjustments to workload and tasks if needed. Reduce demands if workload identified as an issue. Provide additional time to complete tasks if needed, or consider substituting with alternative tasks. Allow flexible/home working. Offer and facilitate alternative methods of communicating tasks and planning of work to assist memory. Ensure a quiet area/room is available. Provide access to counselling services. |

What can we expect from employers?

Employers should ensure that all managers recognise the menopause as both a health and safety issue and an equality issue.

Workplace Representatives and/or Health and Safety Representatives should be pushing for the following.

-

training for managers and staff;

-

clear policies developed in consultation with unions;

-

awareness-raising;

-

ensure risk assessments take the needs of menopausal women into account and that measures to control risks are implemented;

-

establish recognised points of contact within the workplace;

-

improve access to support within the workplace (these can include support groups and buddying schemes); and

-

provide ‘decent’ teaching/management jobs - this means offering flexible working to women, whatever their position.

Employers should recognise their responsibilities under the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act in relation to menopausal women and ensure that risk assessments take the specific needs of menopausal women into account.

What support can members expect from NASUWT?

-

the Union can help by raising awareness of the menopause with employers and challenging discrimination;

-

Representatives can provide confidential advice and support;

-

the Union can provide individualised representation and support to members affected by the menopause and also represent members collectively;

-

the Union can offer workplace/LA training for all members on the menopause. NASUWT has produced bespoke training that can be delivered to members;

-

NASUWT nationally has produced publications supporting members in schools and colleges;

-

NASUWT has provided workshops on the menopause at conferences and seminars throughout the UK.

Relevant policies

Gender and occupational safety and health (GOSH) policy checklist

Purpose of the checklist

NASUWT believes that a fair, transparent and consistent policy, which recognises the importance of a gender-sensitive checklist, is an essential element of effective school management.

Gender-sensitive policies which accord with the provisions in this checklist will help to recruit, retain and motivate teachers whilst minimising the risk of grievance and discrimination.

The checklist sets out the minimum requirements for an effective gender-sensitive policy and is entirely consistent with the statutory provisions of Section 2 of the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974, the Workplace (Health, Safety and Welfare) Regulations 1992 and the PSED introduced by the Equality Act 2010.

It is essential that the employer and trade unions have the necessary negotiating machinery in place to consult and negotiate on health and safety changes and gender equality.

The GOSH ‘gender-sensitivity’ policy should include:

-

an acknowledgment that the employer’s health and safety policy recognises that there are sex and gender differences in occupational safety and health (OSH);

-

a commitment from the employer that OSH will be addressed;

-

a commitment from the employer that they will consult with all workers and their representatives about OSH issues, including risk assessments;

-

a commitment from employers that there will be an appropriate gender balance on the Joint Health and Safety Committee (JHSC) or other consultative bodies;

-

an agreement that OSH will be a standing agenda item on appropriate consultative bodies;

-

risk assessments will be carried out by an appropriately trained staff member and will take account of sex and gender differences. Risk assessments will be carried out for:

-

expectant (at each stage of pregnancy), new and nursing mothers;

-

reproductive health concerns of men and women (e.g. prostate cancer, fertility, menstruation, menopause, endometriosis, breast cancer or hysterectomy).

-

Monitoring and reporting procedures

Adequate monitoring and reporting is central to a ‘gender-sensitive’ policy and should be fed back to all staff and governors via union representatives or other appropriate means. The policy should state that:-

all accidents and incidents will be regularly reported and reviewed. This will include work-related health problems (including those made worse by work);

-

all accident and ill-health statistics will be reviewed at JHSC or other consultative meetings;

-

sex-disaggregated data, showing men and women separately, will be collected and presented at the JHSC or other consultative meetings;

-

a confirmation that women’s health and safety concerns will be taken equally seriously by employers;

-

a commitment to monitor and analyse ill-health statistics, as well as accidents and near misses.

There should be an undertaking that the policy will be monitored and reviewed by the relevant body in conjunction with union representatives on an annual basis.

Model menopause policy

The link below will take you to the menopause policy. It is not advised that activists merely adopt the policy, but adapt it to fit their particular workplace circumstance.

The legislation refers to all UK laws, so you are advised to amend as appropriate.

More information and guidance are available to download on the right/below.

Footnotes

[1] To include ‘and people who menstruate’

Your feedback

If you require a response from us, please DO NOT use this form. Please use our Contact Us page instead.

In our continued efforts to improve the website, we evaluate all the feedback you leave here because your insight is invaluable to us, but all your comments are processed anonymously and we are unable to respond to them directly.