Introduction

Pay and working conditions

England

Northern Ireland

Scotland

Wales

Implications and recommendations

Introduction

Supply teachers are committed, dedicated and highly qualified professionals who provide an invaluable resource for schools. [1] Supply teachers make a vital contribution to securing high educational standards for all children and young people.

Campaigning to secure professional entitlements for supply teachers is a key priority of the NASUWT, together with securing decent pay and working conditions for all supply teachers.

Whilst the Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of supply teachers, it has also spotlighted the growing casualisation of work and the situation for supply teachers, who often have no choice but to obtain work via different supply agencies, leaving them vulnerable to the vagaries of precarious, intermittent and insecure employment.

Supply teachers were hit the hardest as their employment opportunities diminished. In particular, many supply teachers were unable to access furlough pay, even though their work was withdrawn.

In the past, schools engaged supply teachers directly or accessed them from local authority supply pools. Private supply agencies existed at the margins, but not to the extent they do now.

The NASUWT’s annual survey of supply teachers has found that the overwhelming majority of supply teachers (88%) reported that private supply agencies were the only way they could obtain work. Since 2014, the use of supply agencies by supply teachers has risen by 25%. [2]

This is consistent with the National Institute of Economic and Social Research’s (NIER’s) report of the Audit Commission’s finding that the proportion of supply teachers that were supplied through agencies rose from 43% to 54% between 2003 and 2010. [3] More than 70% of secondary school headteachers have increased their spending on agency supply teachers in the three years to 2018.

One of the key factors for the increased expenditure was increased supply agency fees (54% of respondents). [4] However, whilst fees charged to schools have increased, supply teachers have not benefited, and the pay of supply teachers has increasingly lagged behind the salaries of teachers employed by schools.

Agency supply staff teaching expenditure for local authority-maintained schools and academies in England has risen from 48.4% in 2011/12 to 69.7% of supply teacher expenditure in 2014/15. Crown Commercial Services (CCS) estimates that the average agency mark-up was 38%. [5] CCS estimated that this equates to an agency receiving £56 on a charge rate of £200 to the school, with the supply teacher receiving just £101.81. [6]

Pay and working conditions

The increased reliance on agency working for the overwhelming majority led to a reduction in the pay and conditions of service of supply teachers. However, across the UK, there are important differences in the arrangements made in relation to supply and substitute teachers.

England

In general, the disparity between the pay of supply teachers and other teachers, and the precarious financial situation supply teachers have found themselves in, has been further exposed during the Covid-19 pandemic, where many supply teachers have been cut adrift and forced to make tough decisions about their expenditure, or rely on the increased use of credit or the generosity of family and friends to make ends meet. Some supply teachers have been forced to claim Universal Credit and there are those who have had to rely on food banks.

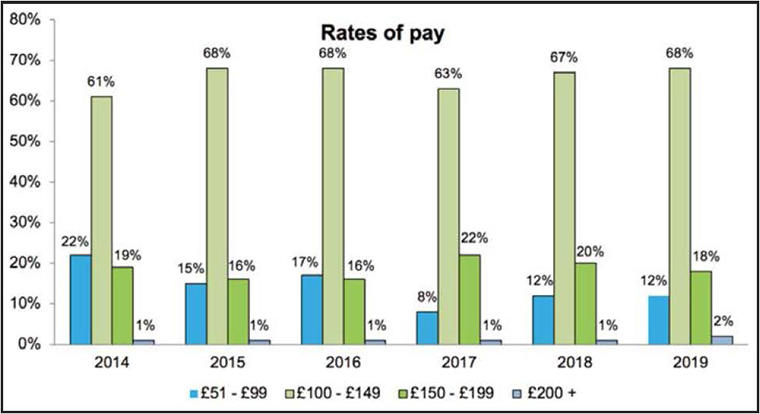

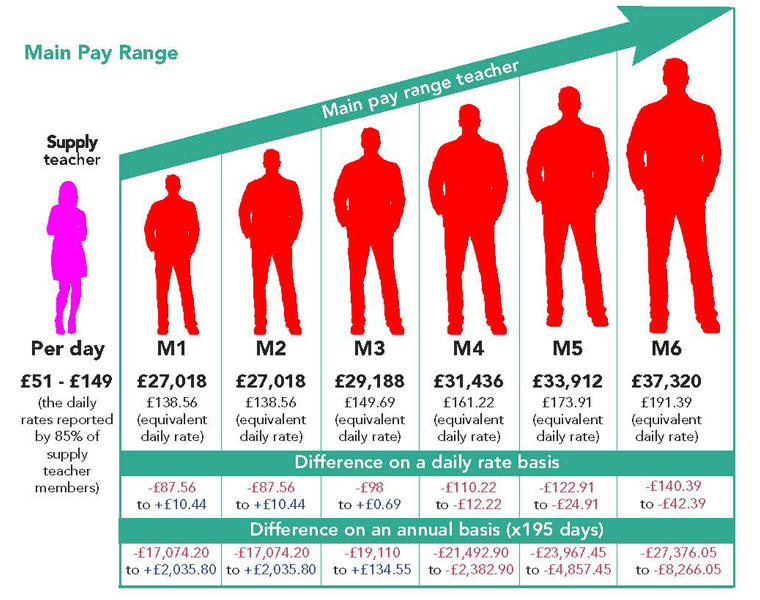

The average daily pay rate for a classroom teacher employed by a school is £207.88. [7] However, the majority of supply teachers report that they are paid between £100 and £149 per day. The majority of supply teachers have not seen their remuneration increase substantially since 2014. [8] We believe that it is now time for the entitlement to national pay scales to be returned to teachers, including those undertaking supply, in England, to ensure that schools in England have a competitive salary structure.

Indeed, in regards to rates of pay for the overwhelming majority of supply teachers forced to undertake work through supply agencies and/or umbrella companies, it still remains the case that two fifths of supply teachers (41%) stated that they were aware of assignments being offered or paid at between £51 and £119 per day from September 2020. Well over two fifths (45%) reported assignments being offered or paid at between £120 and £149 per day, and just over one in ten respondents (11%) reported assignments being offered or paid at between £151 and £199 a day. One per cent said that they were aware of assignments being offered or paid at £50 or less per day.

The National Minimum Wage (which the Government has renamed as the National Living Wage (NLW) in order to appropriate this terminology) is £8.72 per hour. If a supply teacher is expected to teach five lessons per day, they would have to earn at least £43.60 to receive the National Minimum Wage. It is disgraceful that some supply teacher work is being offered at pay rates which are barely above the National Minimum Wage.

This demonstrates that the increased reliance on agency working has led to a reduction in the pay and conditions of service of supply teachers. Rates of pay of supply teachers have remained stagnant for the overwhelming majority of supply teachers, and have been eroded by inflation.

Across the UK, teachers have suffered up to 17% real-terms cuts in pay since 2010. However, in comparison, without the application of the national pay framework, supply teachers have seen their pay plummet relative to other teachers, with no national entitlement to an annual pay award when employed via supply agencies.

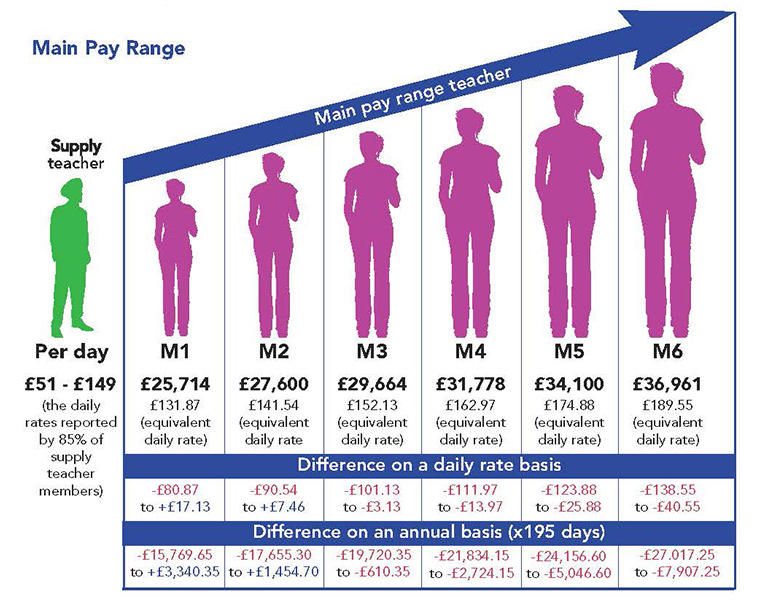

If employed for all 195 days of the academic year, just over two fifths of supply teachers (41%) could expect to earn a salary less than or equivalent to £9,945 to £23,205 per academic year. Such rates of pay would currently see a supply teacher earn over £15,769 to £2,509 below the minimum advisory pay spine (M1), as detailed for teachers in England for 2020/21. [9]

For those supply teachers working at the lower end of the earnings detailed above, this represents an hourly rate of just £7.87 per hour, based on 1,265 hours of directed time for teachers working in local authority-maintained schools, [10] as well as those working in the overwhelming majority of academies.

When set against the NLW for those aged over 23 from April 2021 (£8.91 per hour), this represents a 12% detriment per hour or £1,315.60 over the course of 195 days, based on 1,265 hours of directed time as outlined above.

Even for those supply teachers earning £23,205 as indicated above, this still represents a 9.7% detriment per hour in comparison to a teacher earning the minimum advisory point of M1, based on 1,265 hours of directed time.

When looking at the data for in regards to comparisons between the journey taken by a supply teacher and a teacher working in school, the discrepancies in pay become even more stark. As referenced earlier, assuming a teacher working on a permanent contract receives an annual pay increment, by the time they reach M6, the difference between the pay of a supply teacher and that of a teacher on a permanent contract could be between £27,017.25 to £7,907.25 per year.

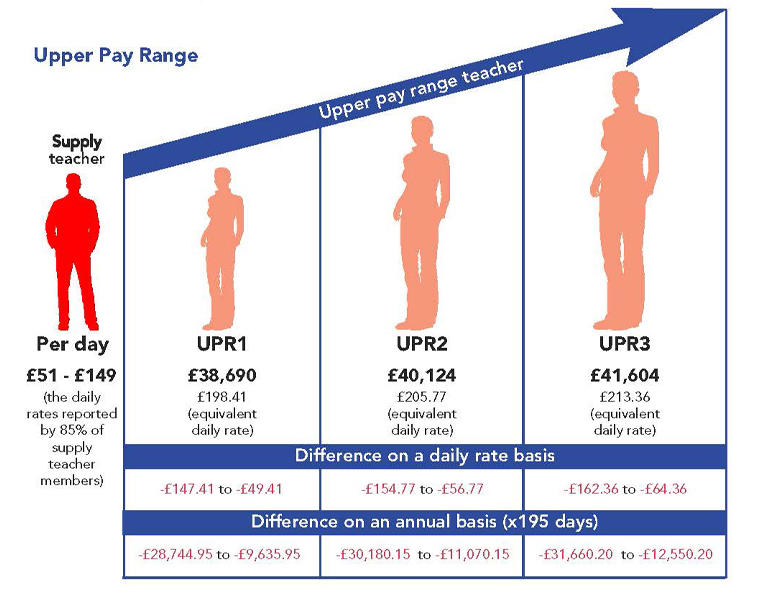

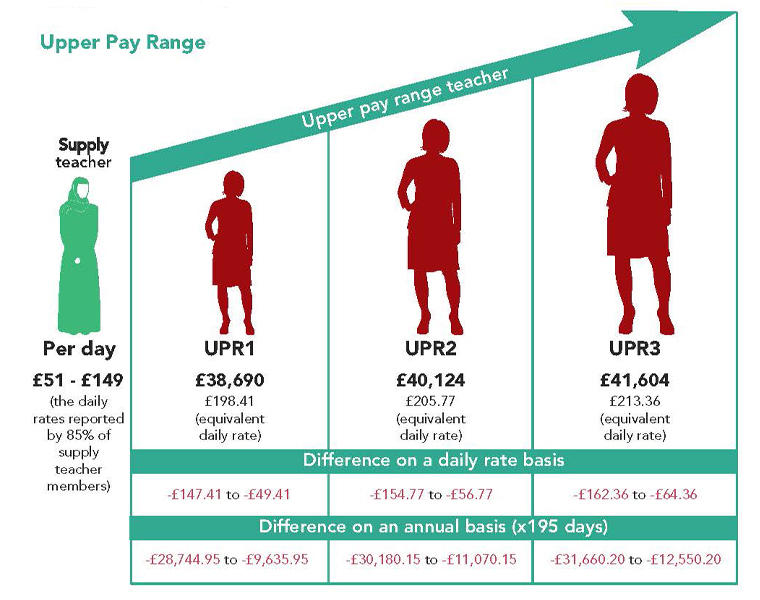

Furthermore, in England, a teacher on a permanent contract would be eligible to go through the threshold, enabling them to access higher rates of pay up to and including Upper Pay Range 3 (UPR3). As a consequence, the differences between the pay of a supply teacher and that of a teacher on a permanent contract are exacerbated, so that the difference could be between £31,660.20 to £12,550.20 per year

Given the vagaries of insecure, intermittent and precarious work for vast swathes of supply teachers, it is extremely optimistic to think that supply teachers will be able to work for all 195 days of the academic year and therefore earn anything near the amounts referenced above. Many supply teachers are therefore earning far less than their permanent counterparts in schools, in spite of their level of experience and expertise.

The impact of inflation - pay erosion since 2014

As stated previously, the majority of supply teachers have not seen their remuneration increase substantially since 2014. [11]

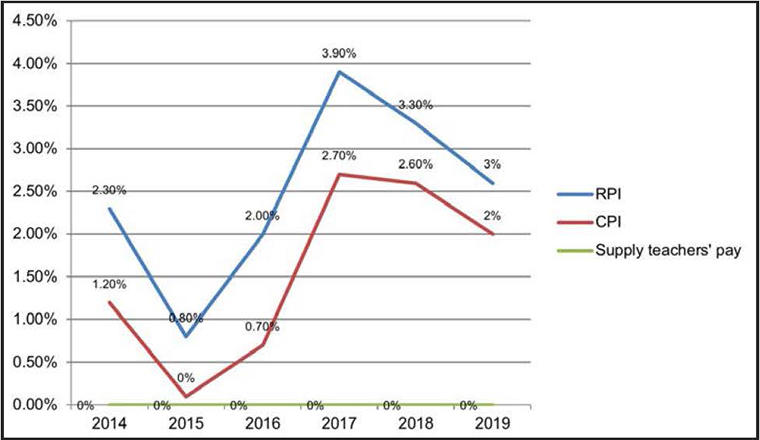

The chart below shows the extent to which the pay of supply teachers has fallen behind price increases, measured by both the Retail Prices Index (RPI) and Consumer Prices Index (CPI), since 2014.

As a consequence, supply teachers’ salaries have reduced in real terms, as measured against CPI and RPI, since 2014.

Since 2014, the value of supply teachers’ pay has decreased between 9.25 (CPI) and 15.3% (RPI) than if supply teachers’ salaries had increased to keep pace with both CPI and RPI rates of inflation since 2014.

Over the same period of time, salaries for MPs rose by approximately 18.2%, including a pay award in excess of 10% in 2015.

The NASUWT advocates that a significant above-RPI inflation increase in salary values over a sustained period is necessary to restore supply teachers’ salaries to a level commensurate with their skills and experience, as the evidence outlined above clearly demonstrates that supply teachers are a profoundly exploited and vulnerable group of teachers, many of whom earn less than the £24,000 per year referenced by the Chancellor in the proposed public sector pay freeze on all teachers’ full-time equivalent (FTE) salaries of £24,000 or over.

As such, the NASUWT calls for all agency teachers to be guaranteed rates of pay commensurate with all other teachers.

Access to the Teachers’ Pension Scheme (TPS)

The situation for supply teachers as agency workers is compounded by the fact that employment by or through agencies is currently not pensionable under the Teachers’ Pension Scheme (TPS), leaving many supply teachers no alternative other than to make less favourable pension plans, including reliance on inferior auto-enrolment pension arrangements. There is a strong argument that supply teachers, working alongside other employed teachers, should be afforded the right to access the TPS.

Northern Ireland

In Northern Ireland, the provision of substitute teachers is overseen by the Northern Ireland Substitute Teacher Register (NISTR), which is operated by the Department of Education (DE). The NISTR is the only mechanism for engaging substitute teachers in all schools in Northern Ireland. It is estimated that 9,000 qualified teachers are registered on the system and it is endorsed by the Government, trade unions and other relevant professional associations.

Substitute teachers are registered through an online booking system which enables schools to book teachers through a regional centralised database. Payment for all approved periods of substitute teaching is then made on a monthly basis at a daily rate through the payroll system run by the DE. The system benefits both schools and teachers as it provides flexibility for the teacher to manage their own availability and travel distances, as well as ensuring they are paid full rates of pay and pensionable service for periods of substitute teaching. [12]

As such, in the 2020 NASUWT Annual Substitute Teachers’ Survey, in respect of rates of pay, 95% reported that they had been paid on the correct point on the teachers’ pay scale for the work they had undertaken during the Covid-19 pandemic. [13]

In addition, the benefits of such an arrangement can be seen in the NISTR Income Support Scheme for Substitute Teachers, which has provided financial support to substitute teachers who no longer have access to work due to the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic and the lockdowns in Northern Ireland. As a result, of those substitute teachers who applied, 91% reported that they were successful in their application and received an 80% payment. [14]

Schemes established in both Scotland and Northern Ireland for supply and substitute teachers during the Covid-19 pandemic are at odds with the advice and guidance issued in by the Department for Education (DfE) and the Welsh Government, which saw swathes of supply teachers in England and Wales not furloughed by their agency/agencies. For those working through a local authority or directly for a school, many supply teachers had their employment assignments terminated with little or no regard to Government advice to the contrary.

Scotland

In Scotland, all supply teachers teaching in maintained schools are employed directly by the local authority. The nationally negotiated terms and conditions of service for teachers working in local authority-maintained schools are contained in the Scottish Negotiating Committee for Teachers (SNCT) handbook. [15]

The SNCT handbook makes a distinction between short-term and long-term supply teachers, which affects pay, supply teachers’ duties and working hours. Irrespective, both short-term and long-term supply teachers are still eligible to be paid on the appropriate point on the main grade scale.

Employment under the terms of the SNCT meant that a significant number of short-term and long-term supply teachers were able to access some level of financial support during the Covid-19 pandemic.

For example, between March and August 2020, under the provisions of the SNCT (20/75), teachers on temporary fixed-term contracts continued to be paid for the duration of their contract, or until the return to work of the absent post for which they were covering. In situations where there was no defined end date, such teachers were paid until the end of the school summer term 2020.

In addition, the Supply Teachers Job Retention Payment (JS 20/78) enabled those supply teachers on a supply list during the 2019/20 school year, who had been engaged for the period 1 January to 31 March 2021, to access some level of financial support based on reference to the average hours worked over the three-month period. As such, 97% of supply teachers who were eligible for the SNCT Supply Teachers Job Retention Scheme received a payment. [16]

Furthermore, eligible supply teachers in Scotland could access sickness allowance under the provisions of the SNCT, which is complementary to the statutory provisions under Statutory Sick Pay (SSP).

Wales

Despite the introduction of the supply teachers framework under the National Procurement Service (NPS), guaranteeing a minimum salary level of at least M1 for supply teachers undertaking assignments for agencies on the NPS framework, it still remains the case that just under a quarter of supply teachers (23%) stated that they were aware of assignments being offered or paid at between £51 and £119 per day from September 2020. Two thirds (66%) reported assignments being offered or paid at between £120 and £149 per day, and just 7% reported assignments being offered or paid at between £151 and £199 a day. Only 2% said that they were aware of assignments being offered or paid at over £200 per day. Two per cent said they were aware of assignments being offered or paid at less than £50 per day. [17]

The introduction of the framework was supposed to provide a minimum floor level for the pay of supply teachers, but the NASUWT is aware that schools are not legally obliged to pay supply teachers the minimum pay rate, as there is no legislation that can enforce this. In addition, schools are not compelled to use the framework.

Furthermore, the Union has been made aware that some of the agencies on the framework are not complying with the requirement to guarantee supply teachers a daily rate equivalent to M1. Instead, some agencies are providing supply teachers ‘off framework’, at rates below the M1 minimum, or supplying them as cover supervisors at cover supervisor rates, and then the school expects them to teach.

If employed for all 195 days of the academic year, just under a quarter of supply teachers (23%) could expect to earn a salary less than or equivalent to £9,945 to £23,205 per academic year. Such rates of pay would currently see a supply teacher earn between over £17,073 to £3,813 below the minimum advisory pay spine (M1), as detailed for teachers in Wales for 2020/21. [18]

When looking at the data in regards to comparisons between the journey taken by a supply teacher and a teacher working in school, the discrepancies in pay become even more stark. As referenced earlier, assuming a teacher working on a permanent contract receives an annual pay increment, by the time they reach M6, the difference between the pay of a supply teacher and that of a teacher on a permanent contract could be between £27,366.05 to £8,266.05 per year.

Furthermore, in Wales, a teacher on a permanent contract would be eligible to go through the threshold, enabling them to access higher rates of pay up to and including UPR3. As a consequence, the differences between the pay of a supply teacher and that of a teacher on a permanent contract are further exacerbated, so that the difference could be between £31,660.20 to £12,550.20 per year.

However, the situation in Wales does suggest a better way of working is possible. For example, the Welsh Government’s 2017 two-year pilot school cluster project, which involved the direct employment of newly qualified teachers (NQTs) who worked across clusters of participating schools, showed that cluster schools experienced an improvement in the quality of teaching in comparison with that previously experienced via commercial supply provision. [19]

As the supernumerary teachers were directly employed by a small number of schools, they were able to become familiar with the pupils, the staff, the school policies and procedures.

The quality and consistency of pupils’ learning experience improved and the emotional wellbeing of learners was addressed by this more stable learning experience, with positive outcomes in pupil behaviour.

These results suggest that where schools and permanent teaching staff at those schools embed supply teachers in the school community and have a regular, professional, collaborative relationship with a pool of qualified supply teachers, the impact on pupil learning can be positive. This is also supported by wider research into effective pedagogy. [20]

In addition, it is hoped that the Welsh Government will heed the recommendations of the Welsh Parliament Petitions Committee, including those recommending a public sector solution and the inclusion of the pay and conditions of supply teachers within the remit of the Independent Welsh Pay Review Body. [21]

Implications and recommendations

The evidence suggests that the failure of regulation in the system is leading to a downward spiral of pay and working conditions for supply teachers. The profit-making market for the employment of supply teachers is not working. It does not serve the interests of taxpayers, pupils or teachers and is at odds with public interests, especially in periods of national crisis. With thousands of supply teachers denied equal pay or the right to work, the NASUWT insists that it is time to end these practices. Importantly, the casualisation of the labour market has impacted upon parents and children and young people. The ability to resource and manage an effective pool of professionally qualified supply teachers that are paid accordingly means a better service for all children and young people.

The NASUWT therefore advocates for a mechanism to be established that directly employs supply teachers, in order to manage the demand for supply teachers effectively, deliver better value when procuring supply teachers, and secure improvements to supply teachers’ pay and other entitlements at work.

The NASUWT believes that governments and administrations must act to prioritise the following:

-

address the situation faced by supply teachers by recommending that all supply teachers who work in state-funded schools, including agency teachers contracted by schools, are remunerated at rates of pay commensurate with all other teachers, with pay rates that reflect experience in the job;

-

deliver a significant above-RPI inflation increase in salary values over a sustained period to restore supply teachers’ salaries to a level commensurate with other teachers, and based on their skills and experience;

-

address the failures of the market and the role of employment agencies in teacher supply, which is having profoundly adverse equalities impacts;

-

where agencies continue to operate, limit the level of financial overhead that agencies may charge schools as part of their fee structures;

- use existing levers to incentivise schools and academies to move towards directly employed or pooled arrangements for sourcing supply teachers.

Footnotes

[1] Please note that reference throughout this report to supply teachers may also include substitute teachers.

[2] https://www.nasuwt.org.uk/uploads/assets/uploaded/cbf2bdf5-8e39-484b-926b1becb8fc586c.pdf

[3] https://www.niesr.ac.uk/sites/default/files/publications/NIESR_agency_working_report_final.pdf

[4] https://edexec.co.uk/ascl-survey-reveals-soaring-cost-of-supply-teachers

[5] https://www.crowncommercial.gov.uk/news/agency-mark-up-and-the-impact-on-temporary-worker-pay

[6] Ibid.

England

[7] Based on data provided on the average teacher (FTE) salary of all teachers in state-funded schools in 2019, found at: https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/school-workforce-in-england

[8] https://www.nasuwt.org.uk/uploads/assets/uploaded/cbf2bdf5-8e39-484b-926b1becb8fc586c.pdf

[9] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/school-teachers-pay-and-conditions

[10] Ibid.

[11] https://www.nasuwt.org.uk/uploads/assets/uploaded/cbf2bdf5-8e39-484b-926b1becb8fc586c.pdf

Northern Ireland

[12] https://www.eani.org.uk/services/northern-ireland-supply-teacher-register-nistr/supply-teachers

[13] https://www.nasuwt.org.uk/uploads/assets/uploaded/0c5ddab4-d803-456e-a4df2ffa4b1aec33.pdf

[14] Ibid.

Scotland

[15] https://www.snct.org.uk/wiki/index.php?title=Table_of_Contents

[16] https://www.nasuwt.org.uk/uploads/assets/uploaded/1feb03f3-f77c-4a9c-ba50603419a0aa3c.pdf

Wales

[17] https://www.nasuwt.org.uk/uploads/assets/uploaded/4e47d9c5-989a-4a33-a3218393d657dcfc.pdf

[18] https://gov.wales/school-teachers-pay-and-conditions-wales-document-2020

[19] Welsh Government (2019).

[20] Stoll et al (2012), Great pedagogical development leads to great pedagogy.

[21] https://senedd.wales/media/neifebkd/cr-ld14241-e.pdf